“I know.” Two words, famously ad-libbed by Harrison Ford after many repeated takes of the scripted “I love you too” line. Two words that evoke love far more powerfully than any hallmarkian sentiment in this or any other galaxy. In all of cinema, in all its rich and romantic history, “I know” is certainly the most romantic ad-lib. And in my estimation, “I know” is high among the most romantic lines, full stop.

From Leia’s perspective, Solo’s pursuit had seemed not motivated by love, but perhaps by a mere desire for conquest.

It is in one of the darkest moments of The Empire Strikes Back, in all of the Star Wars franchise really, when Han Solo replies with those two little words to Leia’s tearful and frighted admission of “I love you.” And in that moment we witness a breaking of character. Not merely the breaking of the fourth wall by Ford with his ad-lib, but the abandonment of a mask behind which Solo had been hiding for so long.

At first blush, it might sound in-character for Solo. Another in a long line of the snappy repartee that had characterized his and Leia’s relationship. But it was more than that. His was a naked and vulnerable return of her statement of love.

Up to that point their relationship had been adversarial, full of romantic friction. Solo had been pressing his suit with Leia, but in a ‘scruffy’ sort of way, the way a scoundrel would. From Leia’s perspective, Solo’s pursuit had seemed not motivated by love, but perhaps by a mere desire for conquest.

If you haven’t ever seen It’s a Wonderful Life, or even if you have seen it, but don’t remember it well, do yourself a favour and go watch it. It is one of those somewhat rare classic films which still holds up amazingly well today. More than that, it isn’t at all the sappy, corny movie that most people assume it is or mis-remember it as.

Far from the cinematic snow-globe that most people mis-categorize it as, It’s a Wonderful Life is surprisingly dark, very witty, and truly entertaining.

Whether they’ve seen it or not, most know it for Jimmy Stewart as George Bailey running through Bedford Falls, yelling “Merry Christmas!”; and of course for the sacharine-sweet Zuzu proclaiming “Teacher says, every time a bell rings, an angel gets his wings!”; all culminating with the tearful reprise of Auld Lang Syne. Those are the images that everybody –everybody who doesn’t remember the film well– recalls immediately upon hearing its name. And I’d agree, if those scenes were indicative of the overall tone of the movie, it would indeed be a sappy mess, hardly worth watching, save for when you desperately need a simple and sweet bit of holiday fluff.

But that is not the feel of the movie! Far from the cinematic snow-globe that most mis-categorize it as, It’s a Wonderful Life is surprisingly dark, very witty, and truly entertaining. The film is thoroughly rewarding even to more refined modern-day audiences. And while it has been elevated to Christmas canon, very little of it actually occurs around Christmastime, and it certainly isn’t your standard holiday fare.

The first two hours of the film are a long, dark study in the psychological torture of George Bailey.

The reason for the dissonance between the perception and the reality of the film is obvious; for decades television network and advertising executives have slavishly adhered to the Law of Classic Films, the law mandating that all, and only, the most clichéd moments of classic films must be repeated, ad nauseum, in every advertisement or reference to said films.

What makes It’s a Wonderful Life such a surprise to the first-time viewer is that, while its runtime is a hearty 130 minutes, all of those oft-remembered, oft-rehashed, and awfully sweet moments occur in the final 7 minutes of the film. While the final few minutes are indeed a super-concentrated distillation of the essence of Christmas, they serve as a well-balanced counterpoint, a satisfying glaze, too sweet on its own, but just perfect as the topper to the body of the film. These clichéd, over-sweet moments work so beautifully well, because the first two hours of the film are a long, dark study in the psychological torture of George Bailey.

First kiss, first bike, first time you swore in front of an adult, firsts are important. The firsts we experience tend to shape our paths through life. That’s not to say that our lives are governed completely by the chance experiences over which we have no control, but if, for example, your first experience with a dog is getting mauled, your path through life will be somewhat different from other puppy-loving children.

Thankfully, not all memorable firsts are traumatic. We all have our keepsake memories that transport us back to our salad days. These warmly remembered moments together define our youth and ultimately have shaped our future selves. One of my earliest formative moments was the first movie I ever watched in the theatre. That experience kindled in me a passion for movies. It’s probably the first and oldest of the passions I still hold today.

I can enjoy watching a movie that I don’t enjoy.

I love movies. My tastes are sophisticated and discerning, yet at the same time incredibly eclectic. I can appreciate a filet mignon of film as much as I can appreciate a peanut butter and jelly sandwich of a movie. Neither is necessarily better, neither could suffice when in the mood for the other. Both can be done quite well, both can be done very poorly. The experience of watching a movie can transcend the movie itself. Without any contradiction, I can enjoy watching a movie that I don’t enjoy.

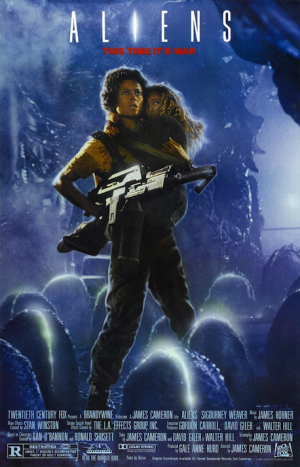

My love of movies started in the Summer of 1986. My mother had remarried the year previous and, while with no step-siblings, I suddenly had a whole new family. One of my new relations was Uncle Steve, or as he offered “Uncle Example”. Uncle Example who, in his mid-twenties, had just as suddenly found himself the occasional custodian of two hellion boys of the ages 9 (my brother) and 7 (me). Uncle Example, with whom “the only rule is that there are no rules”, took us to the first movie I watched in the theatre: Aliens.